August Justus MordtmannAka Dr. Eisenhart, R.A. Guthmann, N.N. Guthmann, R. von A. Duroy-Warnatz (1)Civil Servant, Journalist, Editor, AuthorBorn February 27, 1839, Hamburg, GermanyDied April 30, 1912, Darmstadt, GermanyAugust Justus Mordtmann was a German author, editor, and journalist born in Hamburg on February 27, 1839. He was the son of Andreas David Mordtmann (1811-1879), a diplomat and Orientalist, and the brother of Andreas David Mordtmann II (1837-?), an author and historian, and Johann Heinrich Mordtmann (1852-1932), who, like his father, was a diplomat and Orientalist.

After a short period of study, August J. Mordtmann went to work in a customs office, then in the post office in Constantinople, Hamburg, Metz, and Cologne. I don't know whether his career in civil service overlapped or coincided with his career as an editor and writer, but as of 1870, Mordtmann was still with the post office.

Mordtmann appears to have been friends with or an associate of a German teacher, writer, and journalist named Ernst Otto Hopp (1841-1910). Hopp edited Deutschen (Schorerschen) Familienblatt (translated as Family Blade or Family Paper) beginning in 1881 and founded the weekly Echo in 1882. Mordtmann was an editor with the Familienblatt in 1882-1883 and worked on Echo with Hopp. Mordtmann also edited Görlitzer Nachrichten (Görlitzer News) until 1888 and was editor-in-chief of Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten (Münchner Latest News) until 1902.

August Justus Mordtmann is little known today, but he was a prolific author. His works include the following: Untergang der Hibernia, Kronjuwelen (Crown Jewels), Belladonna, Schlangenring (Snake Ring), Familienschmuck (Family Jewelry), Perlen der Adhermiducht (Pearls of Adhermiducht, 1902), Albumblatt (Album Leaf, Sheet, or Page, 1900), Eine halbe Stunde (Half an Hour), Pater Unselm (2), Das Goldene Vliess (The Golden Fleece), Mass Ingram (2), and Der Vagabund (The Vagabond or The Rover), as well as the following romances: Sonnige Tage (Sunny Day, 1903), Konigin von Golkonda (Queen of Golconda), Jasillü-Tasch: Zwei Geschichten vom "Golden Horn" (Jasillü-Tasch: Two Tales from "Golden Horn"), Märchenprinzessin (March Princess), Die Insel Zipangu (The Island Cipangu, 1899, illustrated by Hugo L. Braune), and a paperback book, Die Abrechnung mit England (The Settlement with England).

Mordtmann wrote one story in Weird Tales. It's called "The Ship That Committed Suicide," and it appeared in the issue for March 1936. I'm fairly certain that the translator was Roy Temple House, who had written a brief review of a German-language collection of ghost stories some years before and who was a regular translator for Weird Tales. The collection of German ghost stories about which he wrote is called Der Untergang der Carnatic: Spukgeschichten (The Sinking of the Carnatic: Ghost Stories), and it was published in 1927 by Deutsche-Dichter-Gedächtnis-Stiftung of Hamburg. The title story, "Der Untergang der Carnatic," is the work of A.J. Mordtmann and was almost certainly the basis for Roy Temple House's translation for Weird Tales. In his review, published in January 1929 in Books Abroad, House called Mordtmann's tale the most realistic of all to appear in the collection. "There are also shudderers by the Grimms, Wilhelm Hauff, Friedrich Gerstäcker, Paul Heyse, and Heinrich Zschokke," wrote House. The illustrations were by A. Paul Weber.

The story "Der Untergang der Carnatic" is an episode in a longer work by A.J. Mordtmann, Die Perlen der Adhermiducht, which was originally published in the magazine Deutschen Romanbibliothet in 1902, then published in hardback in 1905. In his study of ghost stories, Von Gespenstergeschichten, ihrer Technik und ihrer Literatur (On Ghost Stories, Their Art and Their Literature, Leipzig: Schmidt & Spring, 1903), Dr. Benno Diederich described Deutschen Romanbibliothet as having an inclination for telling stories with a spooky atmosphere, and German adventure stories as being less grotesque than their English counterparts. Dr. Diederich gave "Der Untergang der Carnatic" as an example. The title by the way translates as "The Sinking of the Carnatic." My German correspondent, Axel Weiss, describes it as "a ghostship-story taking place in the Antarctic region." By the way, the SS Carnatic was a real ship that foundered in the mouth of the Gulf of Suez in 1869. In addition to Mordtmann's story, the ship is mentioned in Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne (1872).

August Justus Mordtmann died on April 30, 1912, at age seventy-three. I have found out about him only recently after hearing from Axel Weiss, the editor and layout designer for the German magazine Cthulhu Libria and the co-host of a podcast called Arkham Insiders. (Click on the titles for links.) Mr. Weiss wrote to me regarding A.J. Mordtmann because he would like to read the English translation of "The Ship That Committed Suicide" from Weird Tales. I don't have a collection of Weird Tales myself, so I ask: Can anyone provide Axel Weiss with a copy or scan of "The Ship That Committed Suicide" by A.J. Mordtmann, from Weird Tales, March 1936?

If so, please contact me and I will put you in touch with him, or I will forward your reply to him.

Now, on to two issues that have come up in this article.

First, "Der Untergang der Carnatic" is an episode from Die Perlen der Adhermiducht, a story originally published in the magazine Deutschen Romanbibliothet in 1902. According to Dr. Benno Diederich, Deutschen Romanbibliothet had an inclination for telling stories with a spooky atmosphere. I don't know what kind of magazine it was. I have found only five references to that title on the Internet, and all are in German--and in Fraktur script! Der Orchideengarten: Phantastische Blätter (The Orchid Garden: Fantastic Leaves, 1919), a German title, is supposed to have been the first magazine in the world devoted to literature of the fantastic. Could Deutschen Romanbibliothet have been a forerunner? Or was Deutschen Romanbibliothet itself the first magazine of that type? I think this question would be a good jumping off point for a German researcher.

Second, "Der Untergang der Carnatic" was reprinted in the book Der Untergang der Carnatic: Spukgeschichten (Hamburg, 1927). The other authors in that book are the Brothers Grimm, Wilhelm Hauff, Friedrich Gerstäcker, Paul Heyse, and Heinrich Zschokke. A. Paul Weber was the illustrator. (Benno Diederich made some contribution as well.) Farnsworth Wright, editor of Weird Tales, had previously used the book Modern Ghosts (1890) as a source of stories from the Old World. It's nice to think that he could have used Der Untergang der Carnatic: Spukgeschichten for yet more stories, translated of course by Roy Temple House. Instead, Weird Tales reprinted Mordtmann's tale and just one story by Wilhelm Hauff, "The Severed Hand," from October 1925. So who were those other authors, the illustrator, A. Paul Weber, and the contributor, Benno Diederich?

Der Untergang der Carnatic: Spukgeschichten (Hamburg, 1927)

August Justus Mordtmann (1839-1912)

The Brothers Grimm--Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) and Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859), together the Brothers Grimm, are among the most famous storytellers of all time. You can read more about them on your own.

Wilhelm Hauff (1802-1827)--You can read more about him in my posting "Weird Tales from Germany and Austria,"here. Friedrich Gerstäcker (1816-1872)--A traveler, adventurer, travel writer, novelist, and oddly enough honorary citizen of Arkansas, Friedrich Gerstäcker wrote the story "Germelshausen," upon which the Broadway musical Brigadoon (1947) may or may not have been based.

Paul Heyse (1830-1914)--Paul Heyse wrote novels, short stories, poems, and plays and for his work was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1910.

Heinrich Zschokke (1771-1848)--Heinrich Zschokke was a novelist, playwright, historian, journalist, teacher, and civil servant. He spent most of his life in Switzerland.

A. Paul Weber (1893-1980)--Commercial artist, illustrator, lithographer, and painter Andreas Paul Weber was an artist whose work can be called weird without hesitation. There is information on him all over the Internet, including on the website of the A. Paul Weber Museum, here. Benno Diederich (1870-1947)--Benno Diederich was a teacher, scholar, philologist, author, and biographer. Among his works is the aforementioned Von Gespenstergeschichten, ihrer Technik und ihrer Literatur (Leipzig: Schmidt & Spring, 1903) and a biography of Alphonse Daudet. Diederich's daughter was the painter, illustrator, writer, and stage designer Ursula Schuh (1908-1993).

Of all the authors listed here, only August Justus Mordtmann is unrepresented on the Internet by an original work of biography. I hope I have done my part in correcting that oversight. I would like to acknowledge the contribution of Axel Weiss and to thank him for giving me a start on August Justus Mordtmann.

This is probably my last entry on Tellers of Weird Tales for 2014. I hope everyone has a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

A.J. Mordtmann's Story in Weird Tales

"The Ship That Committed Suicide" (Mar. 1936)

Further Reading

Gespenstergeschichten, ihrer Technik und ihrer Literatur by Dr. Benno Diederich (Leipzig: Schmidt & Spring, 1903), p. 176+.

Deutschlands, Österreich-Ungarns und der Schweiz Gelehrte, Künstler und Schriftsteller in Wort und Bild(Leipzig, 1908), p. 321.

Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie, [Volume] 7: Menghin-Potel by Walter de Gruyter (Munchen: K.G. Saur, 2007), p. 189.

Notes

(1) Mordtmann apparently also wrote under a pseudonym which is some variation of the name for a traditional Turkish storyteller, Hodscha Nasreddin.

(2) I have transcribed this list from a source printed in German Fraktur. I'm not sure that I have translated these titles correctly from Fraktur to a modern typeface. My task is complicated by the fact that I know only a few words in German and nothing at all about German grammar. The list is from a book called Deutschlands, Österreich-Ungarns und der Schweiz Gelehrte, Künstler und Schriftsteller in Wort und Bild (Leipzig, 1908), found on the Internet by clicking here. I invite corrections and comments.

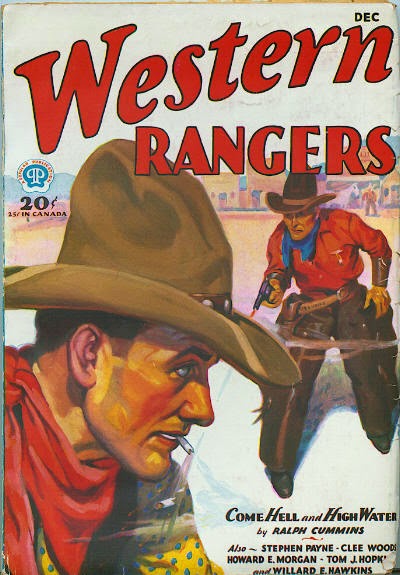

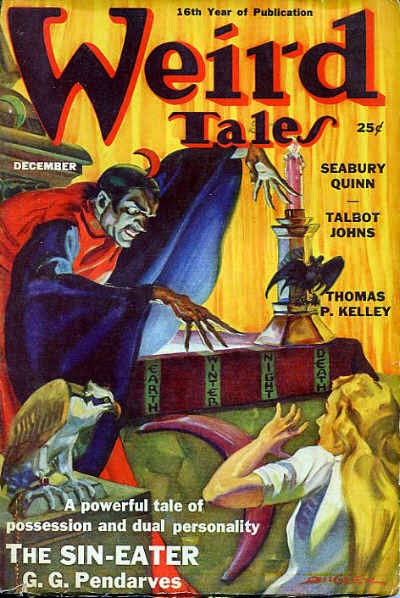

![]() |

| Der Untergang der Carnatic: Spukgeschichten (Hamburg, 1927). |

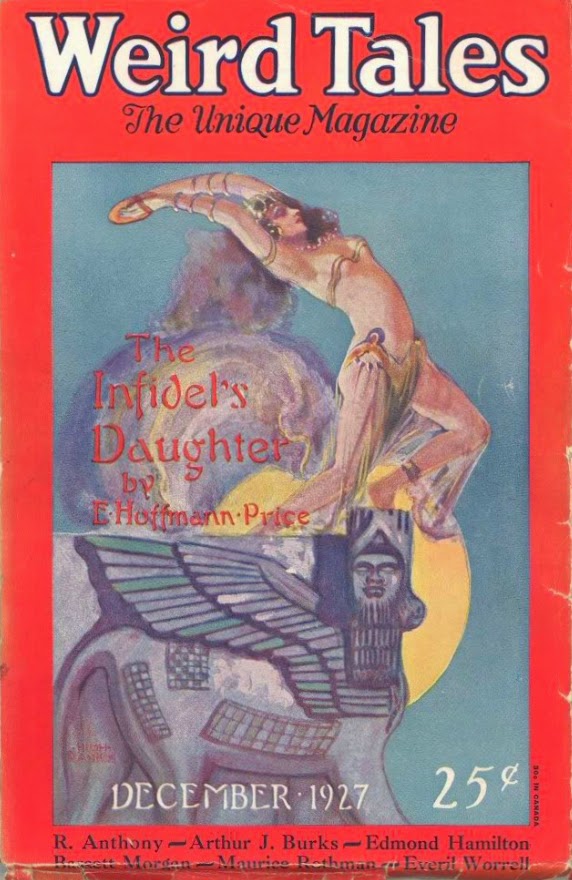

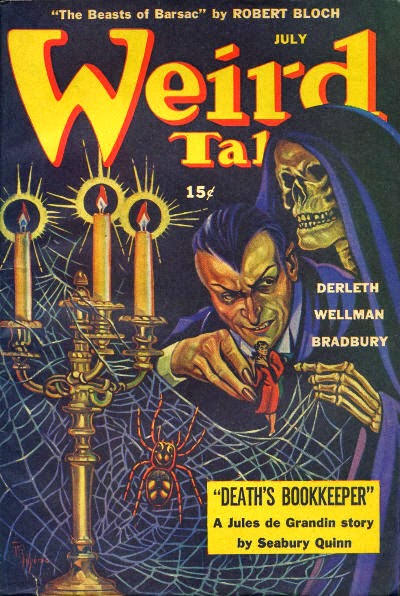

![]() |

| Die Insel Zipangu (The Island Cipangu, 1899), illustrated by Hugo L. Braune. |

![]() |

| A postage stamp showing the work of A. Paul Weber, illustrator of Der Untergang der Carnatic: Spukgeschichten. |

Text and captions copyright 2014 Terence E. Hanley